The Aaron Burr Conspiracy

In July 1804, Aaron Burr (1756-1836), then Vice President of the United States, killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel in New Jersey. Although dueling was illegal in New Jersey and Burr was indicted, he successfully avoided prosecution.

After Burr left office in early 1805, he traveled through the western part of the country. In June 1805, he was at Fort Massac for several days and met there with James Wilkinson (1757-1825), who by that time was serving in the dual roles of commander-in-chief of the army and Governor of the Louisiana Territory. Although nothing further is known of that meeting, a likely topic of their conversation was Burr’s plan to establish a settlement in Spanish territory west of the Mississippi—a plan that potentially included the formation a new independent country out of Spanish Mexico and perhaps also the secession of some western portions of the United States. Wilkinson himself was a paid agent of Spain, a fact that came to light only after his death.

In late 1806, a group of between 50 and 100 men organized by Burr assembled on the Ohio River. In late December, Burr met up with them on Cumberland Island adjacent to Smithland, Kentucky, about 20 miles upriver from Fort Massac. In the meantime, Wilkinson had warned President Jefferson of Burr’s plans, and, on November 26, 1806, Jefferson had issued a proclamation that Burr be arrested. Captain Daniel Bissell, the commander at Fort Massac, would later write that he did not learn of the order to arrest Burr until January 5, 1807. (Note 1.)

In late December 1806, Bissell learned of Burr’s presence at Cumberland Island, although exactly when and how was the subject of dispute. After Burr arrived at the island, Bissell exchanged communications with him through Jacob Dunbaugh, a sergeant under Bissell’s command who traveled back and forth between Fort Massac and Smithland. Bissell was informed that Burr’s expedition would descend the Ohio River on December 29 and berth overnight just above Fort Massac.

Burr’s collection of boats did start down the Ohio on December 29, but, instead of stopping above Fort Massac, passed by that spot overnight and tied up about a mile downstream—close to where Harrah’s Metropolis Casino and Hotel stands today. Bissell had been alerted by his sentinel to the passage of Burr’s boats and paid a visit to him the following morning, December 30.

Several months later, Bissell provided a detailed account of his encounter with Burr in response to a request from the Secretary at War. (Note 2.) The complete text of what he wrote is included on the page “1807 – Daniel Bissell’s Account of Aaron Burr.”

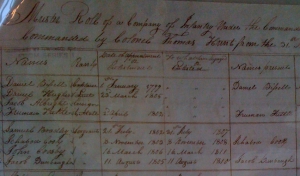

Excerpt of June 1806 Fort Massac muster roll under command of Capt. Daniel Bissell listing Sergeant Jacob Dunbaugh (Muster Rolls of Regular Army Organizations compiled 1784-10/31/1912, National Archives and Records Administration)

Dunbaugh would contend that his communications with Burr were at Bissell’s request and that Burr and Bissell had agreed for Dunbaugh to accompany Burr down the Mississippi River. (Note 3.) Bissell contended that Dunbaugh himself requested a 20-day furlough for the stated purpose of conducting personal business at New Madrid and became a deserter when he went further south with Burr. (Note 4.)

Burr was finally arrested later in January 1807 and, in September and October of that year, stood trial for treason in Richmond, Virginia, where he was acquitted of that charge. Dunbaugh and Bissell both testified at the trial, and Bissell was questioned about the testimony Dunbaugh gave about what took place at Smithland and Fort Massac. (Note 5.)

Beyond the information relating to Burr, Bissell’s trial testimony reveals that he had “lost a son” about November 1, 1806 (which was in the midst of his civil litigation with William Chribbs) and that Mrs. Bissell had remained ill through the end of that year. (Note 6.) From these circumstances, one might surmise that the baby died at birth or shortly after, and that Bissell’s wife was still recovering at the end of December. (The account Bissell provided to the Secretary at War also mentioned that his wife was at Fort Massac at that time.)

To New Orleans

William Chribbs also would travel down the Mississippi River in early 1807, well aware of Aaron Burr’s venture but not as part of it.

It is hard to imagine that Chribbs would have continued to live with his family at Fort Massac after October 20, 1804. Once he had sought to have his wife indicted for conspiring in an attempt on his life (an indictment that remained open until August 1806), being part of the same household must not have been an option either from his point of view or Eliza’s. He was certainly at Kaskaskia during part of this time and was probably there for the December 1806 court session.

He may have spent time at Smithland, as well, as Bissell believed. Subsequent events suggest that Chribbs was at Smithland when Burr was there at the end of December 1806.

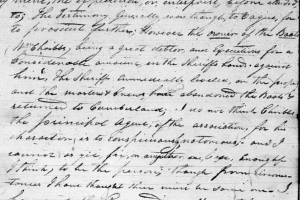

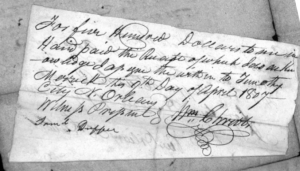

Excerpt of Jan. 24, 1807 letter from Bissell to Secretary at War concerning Chribbs’s barges (Document B201, Microfilm M221, Roll 3, National Archives and Records Administration)

On January 18, 1807, two barges owned by Chribbs were detained by Bissell as they passed by Fort Massac on their way from Smithland to Ste. Genevieve to pick up shipments of lead. (Note 7.) The mostly empty barges contained some barrels of pork and a few saddles, bridles, and saddlebags.

Although the Ohio River is within the state of Kentucky, once the barges were docked at Fort Massac, they were within Randolph County of the Indiana Territory. Bissell had Frederick Graeter (Graetere), a Randolph County justice of the peace, question the crew members about the purpose of their trip but decided that there were insufficient grounds to conclude they were part of Burr’s venture.

Bissell, however, knew that Chribbs owed money on Randolph County court judgments—perhaps including Bissell’s own civil suit against Chribbs for malicious prosecution. The Randolph County sheriff was informed of the presence of Chribbs’s barges in the county, and he took possession of them to pay judgments against Chribbs. Bissell recounted all of this in a letter to the Secretary at War on January 24, 1807, the complete text of which is included on the page “1807 – The Seizure of Chribbs’s Boats.” The following portion of that letter, which relates to Chribbs, has been edited for readability.

[T]he owner of the boats, Wm Chribbs, being a great debtor and executions for a considerable amount in the Sheriff’s hands against him, the Sheriff immediately levied on the property, and the masters & crews have abandoned the boats & returned to Cumberland. I do not think Chribbs the principal agent of the association, for his character is too conspicuously notorious; and I cannot as yet fix on any other base enough I think to be the person; though from circumstances I have thought there must be some one.

Whether or not Chribbs himself was on his boats when they were seized, he departed for New Orleans about that time. He arrived there by March 1807, as can be seen from the litigation records that follow.

On June 19, he wrote a letter from New Orleans to the Secretary at War that touches on the Burr conspiracy, Sergeant Dunbaugh’s version of events at Smithland and Fort Massac, and his own dispute with Bissell—including the seizure of his boats. (Note 8.) Following is the complete text of the letter:

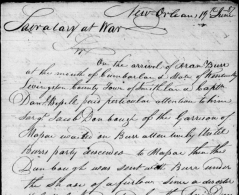

Excerpt of June 19, 1807 letter from Chribbs to Secretary at War (Document C289, Microfilm M221, Roll 5, National Archives and Records Administration)

New Orleans 19th June -07

Secretary at War

Sir

On the arrival of Aron Burr at the mouth of Cumbarland State of Kentucky Livingston County Town of Smithland Captn Danl. Bissell paid perticular attention to him. Sargt. Jacob Donbaugh of the Garrison of Massac waited on Burr attentively until Burrs party descended to Massac then the Dunbaugh was sent with Burr under the shade of a furlow. Since a deserter & latterly I understood by the said Dunbaugh at this place that Bissell reported him dead not withstanding that Captn. Danl. Bissell actually don every thing perhaps safely in his power to facilitate the scheam of Burr. He actuly stopt of mine two keel boats, two flats & one barge under the pretext of my being of Burrs party until I had to compromise suits in court for his boarding my barge with a qanditty of soldiers & would have taken my life had not Captn. Francis Johnston entiferd & for the burning of my plantation hous & tradeing house also & himself with a number of soldiers would not suffer me to enter my own dwelling house whare my wife & famaly were & since which time he has finily seperated us she remains at Massac whare he furnishes her with the baking for the troops of that garrison & a soldier baker from the garrison.

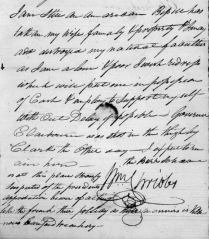

Excerpt of June 19, 1807 letter from Chribbs to Secretary at War (Document C289, Microfilm M221, Roll 5, National Archives and Records Administration)

After the law suits were dismist Bissell had nothing to say on acct. of Burr twenty men were at my service & every attention then paid me. I could receive no assistance from so base & treacherous a charractor as I knew by Col Matthew Lyons letter to me Bissell had stated & asserted many fallshoods against me. My four boats & property were lost. I proceeded to this place with my barge had som conversation with Genl. James Wilkinson. My opinion previous to this was confirmed. I had been at St Louis. He would not cross to Kentucky where he formerly visited weekly [ ] his sceam of gallantry with prosstitutes there I could put him in the pennatentiary. I have been applied too join a number of Spaniards & [ ] som places on [ ] part of the Missura. Burr also applied to me. I am still an Amarican. Bissell has takan my wife famaly & property & I may add destroyed my natural faculties as I am alone & poor. I wish redress which will put me in possession of cash & employ to support myself without delay if possible. Governer Claibourn was shot in the thigh by Clark the other day. I expect to remain here. The Burr scheam is at this place strongly suspected of the presidents approbation. Bewer of acting like the french their pollicy as [ ] manners is villenous barefaced treachery.

[signed] Wm Chribbs

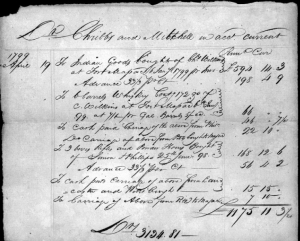

1799 Chribbs and Mitchell account with Wilkins (Civil suit record no. 518, The Louisiana Purchase: A Heritage Explored, LOUISiana Digital Library, Baton Rouge, La.)

Chribbs & Mitchell’s Debt to Wilkins

In his March 5, 1805 letter to Charles Wilkins described in Part VII, Chribbs had discussed his continuing business relationship with Charles and his brother John. In 1807, Chribbs still owed the Wilkins brothers substantial sums. Aware that he was now in New Orleans, John Wilkins initiated a lawsuit against him and Robert Mitchell there in March 1807 to recover more than $3000. (Note 9.) Shown here is a page listing the account that Chribbs had maintained with Wilkins dating from 1799.

Daniel Elliott, an agent for Wilkins, provided a deposition in support of the claim. Elliott provided numerous details about Chribbs’s activities:

[I] did about sixth or seventh day of March last past present the account here to annexed the ballance of which is $3134 81 cents to the Defts that the said Defts readily confessed that they had been partners in trade at the time of receiving the goods works and merchandize . . . and the said Chribbs agreed that upon his arrival at New Orleans to confess a Judgment in favor of the Petitioner for the same.

[A]bout the time of the above conversation [I] also heard from the said Chribbs and Mitchell the following facts respecting the state of their affairs & by that the said Chribbs had placed in the stock of said partnership three thousand pounds and the said Mitchell five hundred pounds—that they yet owned as partners fifteen hundred acres of land in Tenassee & three tracts in the Ilinois and that the ballance of their property being merchandize estimated at about four thousand dollars was destroyed by fire.

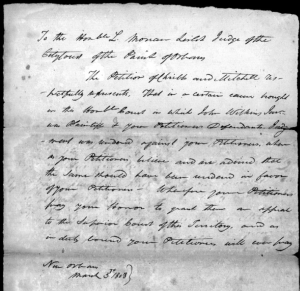

March 5, 1808 order allowing an appeal of the Wilkins judgment (Civil suit record no. 518, The Louisiana Purchase: A Heritage Explored, LOUISiana Digital Library, Baton Rouge, La.)

This deponent further heard said Mitchel say that his said partner had once set out for Pittsburgh to make the Petitioner a payment but that he believed he had stopped in Tenessee and gambled away the money. . . .

I have reason to believe & do believe that Chribbs one of the within named Defendants was indebted to John Wilkins Jun in a considerable sum previous to his connection in trade with Mitchell. I have also reason to believe and do believe that several remittances made by the firm of Chribbs & Mitchell were under the direction of Chribbs applied to the extinguishment of his own private debt contractd as aforesaid before his partnership with Mitchell. I have no idea of the amount of the old debt of Chribbs on the amt of the remittances.

The case documents reflect that Chribbs & Mitchell were represented by attorney Abner L. Duncan and that a judgment was entered in favor of Wilkins on April 28, 1807, based on Chribbs’s confession of the debt. In apparent contradiction to that strategy, the defendants subsequently requested an appeal. On March 5, 1808, the court permitted the appeal, although the result of the appeal isn’t known.

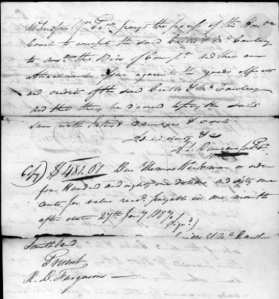

Excerpt of 1807 Kirkman claim with copy of note (Civil suit record no. 533A, The Louisiana Purchase: A Heritage Explored, LOUISiana Digital Library, Baton Rouge, La.)

Chribbs & McCawley’s Debt to Kirkman

At the same time that Chribbs was defending his partnership with Robert Mitchell, he was also attempting to keep his business with McCawley afloat. To that end, on January 27, 1807, he signed a note to Thomas Kirkman promising to pay $481.61 one month later. (Note 10.)

When payment was not made, Kirkman sued Chribbs & McCawley in New Orleans. In this suit, Abner L. Duncan represented Kirkman, even though he was apparently representing Chribbs & Mitchell at the same time in another case. Chribbs was represented by attorney Abraham R. Ellery. On April 28, 1807, Ellery filed Chribbs’s denial of Kirkman’s claim.

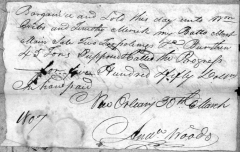

March 30, 1807 bill of sale for barge “Progress” (Civil suit record no. 533B, The Louisiana Purchase: A Heritage Explored, LOUISiana Digital Library, Baton Rouge, La.)

Although the documents in the case file don’t contain a judgment, there are references to an attachment proceeding, which indicates that judgment was entered against Chribbs.

That conclusion is reinforced by a companion proceeding involving Timothy Merrick. (Note 11.)

On April 22, 1807, Merrick filed a claim on a barge named “Progress.” He was represented by Ellery in the case. The claim stated that Merrick

April 9, 1807 assignment from Chribbs to Merrick (Civil suit record no. 533B, The Louisiana Purchase: A Heritage Explored, LOUISiana Digital Library, Baton Rouge, La.)

claims as his own property & legally acquired by him, a certain Barge called Progress, of which [he] is at present master, together with her tackle, apparel & furniture, which said Barge is at present unlawfully attached & detained by the Sheriff of this Parish at the suit of a certain Thomas Kirkman & by process [ ] from this Honorable Court . . . .

Based on the documents in the case file, on March 30, 1807, Merrick and Chribbs had jointly purchased the barge from Andrew Woods. Then, on April 9, Chribbs sold his interest in the barge to Merrick.

It’s not clear why, but the court ordered the barge to be sold with the proceeds to be distributed among various parties.

Copyright 2012-2014 Gregory Hancks

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 United States License.