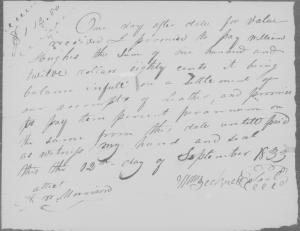

Sept. 12, 1833 note from William Becknell to William Hughes (Cooper County, Mo., Circuit Court Case Files, Box 6, Folder 18 (Microfilm C37277), Missouri State Archives)

Becknell’s appointment as justice of the peace ended in 1831, and his service as state representative ended in 1832. His public life was at a lull for several years.

In September 1833, Becknell signed a note to pay William Hughes $112.80 on account of leather and other goods. (Note 1.) Upon Becknell’s failure to pay, the following June, Hughes obtained a judgment in that amount in the Cooper County Circuit Court. (Note 2.)

Becknell’s failure to pay his debt may demonstrate a financial strategy rather than his poverty. In January 1834, the Becknells had sold their property at Little Arrow Rock (present-day Saline City) for $500. (Note 3.)

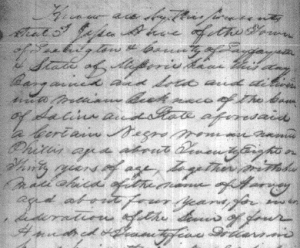

Feb. 6, 1834 sale of slaves from Jesse Nave to William Becknell (Red River Co., Tex., Deed Book C, p. 374)

The following month Becknell travelled to Lexington, Missouri, to purchase two slaves: “Phillis aged about Twenty Eight or Thirty” and her four-year-old son Harvey. (Note 4.) The price was $425. (The transaction was not recorded until April 20, 1840, in Texas.)

Then, in the fall of 1835, William and Mary Becknell moved to Texas, which at that time was still part of Mexico. According to a letter he wrote the following year, they emigrated with “many others” from Missouri and had intended to “proceed on to the interior of Texas but by unavoidable occurances” were compelled instead to settle with their families just south of the Red River. (Note 5.) What prevented the settlers from going further south, according to Becknell, were the “hostile intentions” of Indians, specifically the Caddo, who he claimed had been stealing horses and could be expected to murder settlers.

Becknell’s perspective on leaving the United States to live in Mexican territory probably cannot be immediately understood looking back from the twenty-first century. There was hardly any doubt that his destination was Mexican territory because the 1819 Adams-Onís Treaty between the U.S. and Spain had already established the border where the eastern boundary of Texas remains today. Nevertheless, some Anglo-American settlers just south of the Red River believed they fell under the jurisdiction of Arkansas. (Note 6.) Becknell himself seemed to think that the U.S. government would act to support Americans who had emigrated to northeast Texas. In his 1836 letter cited above, he stated that he was “led to believe the United States would consider it a duty incumbent on them to repell the [Indian] aggression as quick as possible and for that purpose establish a foart on our frontiers boarders.” In any event, Becknell had no immediate prospect of acquiring land in Texas, with the result that he would probably have to live as a squatter.

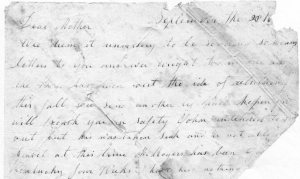

Excerpt of Sept. 28, 1836 letter from Mary Jane Rogers to Mary Becknell: “the Boys has given out the ide of returning this fall” (private collection)

All five of the Becknells’ children also moved to Texas eventually. The youngest, Cornelia (about seven at the time), presumably accompanied her parents. In the fall of 1836, Mary Jane Rogers (then 21), still living in Missouri, wrote a letter to her mother that gives more details about the family. (Note 7.) Mary Jane described her own sons Edward (5) and William (3) as anxious to see their “papa” (John Kirtey Rogers), who at that time had been gone to Kentucky for more than a month. She said that her brothers William (19) and John (18) (“the boys”) had intended to return to Texas that fall but would not because John’s horse “was taken sick.” Although not mentioned in the letter, at the time of writing Mary Jane must have been pregnant with her third child, Sarah Elizabeth Rogers, who is listed on the 1850 U.S. Federal Census as 14 years old.

It is believed that the other Becknell daughter, Lucy, married Francis Jackson Carter (F.J.C.) Smiley in Missouri about 1835 and emigrated to Texas about the same time as her parents. (Note 8.) As described in Part X, F.J.C. Smiley testified that he arrived in Texas on December 22, 1835, and consequently received a land grant as a head of household.

There is no indication that Mary Becknell’s mother, Elizabeth Prichard, moved to Texas. In 1839 as a resident of Callaway County, Missouri, she deeded her property there to her grandsons Jesse Evans and William Evans, the two oldest sons of her daughter Hannah. (Note 9.) It is likely that Elizabeth died not long after. (Note 10.)

Texas War of Independence

The Becknells arrived in Texas just in time for open hostilities between the Mexican government and the Texians, which began with the Battle of Gonzales on October 2, 1835.

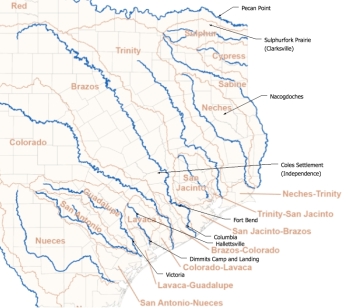

Map showing location of Jonesboro on the Red River and “Becknell’s Prairie” 20 miles to the south (5 miles west of Clarksville)

Davy Crockett, a U.S. congressman from Tennessee, lost his bid for reelection in August 1835 and set out for Texas the following November. Crockett crossed the Red River into Texas at Jonesboro and, according to local tradition, spent his first night there at the home of John Stiles. (Note 11.) It is also said that Crockett met up with his “friend” William Becknell while passing through the area. It may well be true that Crockett made a point of meeting fellow-frontiersman Becknell, but it is unlikely that the two had ever met before. Becknell had not been east of St. Louis since the War of 1812, and Crockett was making his first trip west of the Mississippi.

The local history that chronicles Crockett’s journey through northeastern Texas also assumes that Becknell was already living about five miles west of Clarksville on the land (“Becknell’s Prairie”) that he would later own and call home. Although it is possible that the Becknells settled at this location immediately upon their arrival, there is no contemporaneous record of that fact.

In the meantime, the political and military conflict escalated between the Texians further south and the Mexican government. On March 2, 1836, at Washington-on-the-Brazos, the Texians declared their independence. Then, on March 6, the Mexican army overcame a Texian force (including Davy Crockett) at the San Antonio mission called the Alamo.

On April 1, the president of the newly declared Texas republic, David G. Burnet, issued the following proclamation to the “Citizens of Texas Residing in the Municipality of Red River.” (Note 12.)

The enemy is advancing upon your brothers, their hands still warm with the blood of our gallant brothers slaughtered in the Alamo. In the name of Texas, I exhort you citizens of Red River to repair with alacrity to the field, and chastise the audacity of the invaders. . . . Your all is at stake, your wives, your children, all that is dear and sacred to freemen summon you to the field. Your inherent gallantry will promptly obey the call.

The decisive Battle of San Jacinto near present-day Houston took place only three weeks later, on April 21. Tradition in Red River County describes the arrival of William Becknell and others at San Jacinto within hours after that battle and the role they played in keeping custody of the new prisoner, Mexican General Santa Anna. (Note 13.) Because the general remained in custody for an extended period, it is conceivable that Red River residents guarded him at some point, but historical records tell a different story about Becknell’s own part in the Texas revolution.

Red River Blues

On May 28, 1836, from Pecan Point on the Red River, Becknell wrote to Texian General Sam Houston describing the formation of a militia company there by the settlers on April 28. (Note 14.) Becknell, who was the commanding captain, enclosed a muster roll of the company. The letter was delivered to Brigadier General Thomas J. Green in Houston’s absence. In the letter, Becknell began by admitting that he was “an intire stranger” to Houston and expressed concern about the dangers posed to the settlers by the Indians. The letter made no mention of Burnet’s April 1 proclamation or the conflict with the Mexican government. Instead, the letter and muster roll offered to guard against Indian attack and to build a fort somewhere in the watershed of the Sabine and Trinity Rivers.

Map of east Texas rivers and watersheds with locations related to Becknell’s service in the Texas War of Independence

It is apparent from the letter’s language and handwriting that it was penned by a hand other than Becknell’s. Comparison with letters written by his wife suggests that it was Mary Becknell who acted as his secretary.

The muster roll (which was not written by Mary Becknell) listed the Becknells’ two sons as privates in the company but noted that both were “absent on business” on the date of muster. In fact, the two young men were in Missouri at the time, as described in Mary Jane Rogers’s letter written the following autumn.

Green responded to Becknell’s letter on June 25, 1836, from the northern division headquarters of the Texian army at Coles Settlement (present-day Independence). (Note 15.) Green said that Becknell’s offer of service was “much wanted” and gave alarming descriptions of the “Mexicans with a larger army” on the southern frontier “fast advancing on our country” as well as Indians in the north in “hostile array.” Green authorized commissions for the members of Becknell’s company, directed that the company proceed to the army’s headquarters, and encouraged Becknell both to add volunteers and to engage hostile Indians on the way.

What is known about the activities of the Red River Blues, as Becknell’s company was called, is recorded in documents that were kept by Green and eventually donated to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (Note 16.) Beachum has detailed the company’s activities, which will not be fully recapitulated here. (Note 17.)

If Becknell and his company were seeking glory in battle, they would be disappointed. After leaving Red River country in mid-July, the company travelled 350 miles in little over a month to reach Victoria (probably by way of Coles Settlement). This was about the same distance from the Red River as Arrow Rock, Missouri. The enemy encountered was not any force of Indians or Mexicans but disease, which caused the death of at least one private.

In early September, Becknell received orders from Green to go up the Lavaca River and arrest John Hallett (Hallet), who was described as a “notorious thief and villain” who had been stealing horses and cattle. Green had already sent another force under Captain Southerland for the same purpose. A week later, Becknell reported that he had found Hallett but that Southerland had arrived there first, had already taken possession of the disputed horses, and had no “wish to cooperate” with Becknell. The few cattle that were to be found were left with nearby settlers in accordance with Southerland’s orders.

Becknell’s letter states that Hallett had been “brought in,” but Hallett’s ultimate fate was not recorded. Nor is it known for certain which John Hallett was arrested.

John Hallett and his wife Margaret had emigrated to Mexican territory by 1813 and, by 1818, were living at Goliad, Texas. In 1833, they obtained a league of land on the Lavaca River in Stephen F. Austin’s colony. (Note 18.) According to local tradition, Hallett died in March 1836 as a result of the Mexican army’s sweep through the area. It is also believed that the Halletts’ oldest son, born about 1813, was also named John and died by 1837. Whether it was the husband or son of Margaret Hallett that Becknell arrested, within a few years, she donated land for the formation of a town in Lavaca County, and the family name lives on as the county seat of Hallettsville.

Republic of Texas Election

On September 5, while the Red River Blues were in the vicinity of the Lavaca River, the new Republic of Texas held an election for president, vice president, and congress. As described by Beachum, the Red River region was allotted three representatives, and residents serving in the army voted from where they were stationed in the field. (Note 19.)

Becknell and two other men (Mansell Matthews and George W. Wright) received the largest number of votes from Red River companies. The three men assumed that they would be the winners of the entire Red River tally, which would include residents voting back home, and travelled to Columbia (present-day West Columbia) to attend the first congressional session on October 3.

Although Becknell began service as a representative in the new congress, within a week the official results from the Red River arrived, which showed that Collin McKinney (along with Matthews and Wright) had received the most votes. On October 12, the House of Representatives seated McKinney in place of Becknell, a legislative action that Becknell himself generously supported. (Note 20.)

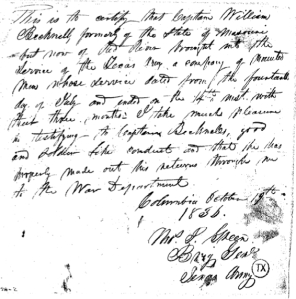

Oct. 19, 1836 certification by Thomas J. Green of Red River Blues service July 14 to Oct. 14 (Claim No. 1080, Republic Claims, Texas State Library and Archives Commission)

On October 14, the Red River Blues were mustered out of service, and Becknell headed north for home. On October 18, from Fort Bend (on the southwest edge of present-day Houston), he sent an awkwardly drafted letter to Green. (Note 21.) The brief letter, which is in Becknell’s own handwriting, offered his services to command the northern part of the new republic’s military forces.

On November 4, from Nacadoches, Becknell wrote to Green again, this time obtaining clerical help to compose a more lucid message. (Note 22.) In the letter, Becknell promised to undertake some previously agreed-upon “excursion” with his “company of old rangers,” probably to investigate Indian activity to the southwest of the Red River territory. The letter expressed his view that it would be prudent to establish a fort in the vicinity of the three forks of the Trinity River, which he would be willing to command. Becknell’s recommendation to establish a fortification in or near present-day Dallas County, however, was not acted on.

Copyright 2012-2014 Gregory Hancks

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 United States License.